Why There Is No Place for ‘Prompt’ Talk in My Classroom

Following my previous article on ISTE, I came to realise just how divisive the talk of generative AI is in schools. I’ve had some lively discussions with my teaching colleagues. One of my most notable and typical was with a long-term colleague and friend, a History teacher at my school who thinks less than favourably about the AI introduction into the classroom. She had two main issues with its use:

- Personally, she’s never considered herself tech-savvy, and the bombardment of AI jargon and technical terms makes it seem like an impenetrable fortress she’d rather not attempt to scale.

- She believes that students with basic tech skills use AI to cheat, undermining genuine education.

I didn’t disagree with her on either point. The realm of AI technology is constantly evolving at a breakneck speed; miss a single update on social media, and you can quickly feel as if you’re lagging behind, stuck in a cycle of perpetual ignorance. Similarly, I’ve also been inundated with assignments that were clearly churned out by students in a mere five minutes. These submissions often lack any genuine reflection of the student’s own thoughts and opinions and are usually prefaced with the telltale phrase, ‘Of course, I’d be happy to help with that.’

However, I wanted to persuade her—and perhaps prove to myself—that there is another side to this story.

I once more decided to create a far-from-scientific, simple experiment.

The Experiment

I dispatched my sixth-formers to the computer room, tasking them with tackling one of the most challenging essay questions on trade blocks—a subject I had not yet covered in class. While they were permitted to consult their textbooks and use ChatGPT, conversing with one another or asking me questions was strictly off-limits.

Just when my students thought I had reached the pinnacle of diabolical and unfair teaching methods, I unveiled my pièce de résistance. I reached into my bag and distributed hefty booklets entitled ‘200 Best ChatGPT Prompts for Essay Writing,’ but only to half of the class. The other half received a diminutive, forlorn-looking piece of paper with the simple directive:

‘Do not use any prompt; CHAT with ChatGPT.’

What they didn’t realise was that I had purposefully divided them into two cohorts: the ‘prompters,’ who leaned towards computer science in their academic preferences, and the ‘resource-less’ group, who were more inclined towards the arts and humanities.

I then spent the next 5 minutes dealing with ensuing sulking and threats of parental involvement from the unjustly treated group, which certainly wasn’t helped by the gloating booklet holders.

However, there was one more twist: I wanted to mark the answers without knowing who had written them. So, for the first time in over 15 years of education, I was able to answer ‘no’ to the students’ favourite ridiculous question of “Do I write my name on my test paper?”

They had one hour

The Results

Once again, the results were enlightening.

The ‘prompters’ studied their prompt booklets, quickly typed, and smugly finished within 20 minutes. They then asked if they could end the test and get on with other homework.

The ‘resource-less’ group were panicked and stressed but absorbed and needed the full hour, during which they fiercely chatted back and forth with ChatGPT.

I asked all students to print their answers and hand them in without their names on them.

Their Answers

The ‘prompters’ churned out uniformly competent essays, impressively so given the mere 20-minute investment. However, these compositions lacked the individual flair and perspectives of their authors. They were devoid of original thought, and most tellingly, I couldn’t correctly associate a single essay with its rightful creator.

What the ‘resource-less’ produced, however, was a mixed bag ranging from poor to exceptional. Unlike the other group, all of their answers showed originality and certainly did possess the style of their creators. From this group, I could match all but two answers to their creators.

Conclusion

The essays created by ‘chatting’, born of genuine two-way interaction, provided an authentic mirror of their authors’ abilities. Students who find critical thinking challenging also struggled to extract pertinent information from ChatGPT. Conversely, those who excelled in analytical reasoning—whom I’d consider the genuine humanities students—were able to engage with ChatGPT to obtain accurate information and nuanced insights. They then articulated these in balanced, evaluative essays. While these pieces took longer to craft than those of the ‘prompters,’ they were often of exceptional quality and thought-provoking depth.

Since then, talk of prompts is now frowned upon in my lessons. ‘Banned’ would be too strong; indeed, there is a time and a place for ease, speed and efficiency that comes with prompting, and undoubtedly, prompt engineering is a skill that my students need to be taught. However, as I’m first and foremost a humanities teacher, I don’t believe I am the best one placed to teach it.

Sharing my experiment:

Of course, I couldn’t resist taking these results back to my history teacher colleague. As we teach many of the same students, she could also draw meaning from the results.

I think I won her over, and collectively, we drew this conclusion:

Effective ChatGPT use is a skill, but the skill isn’t technological.

Incidentally, the history teacher is now quite an AI advocate and happily pronounces that she teaches AI skills in all her lessons. She proudly claims she has done so for the last 20 years. That skill is critical thinking.

Tag:AI, aiineducation, Chatgpt, ChatGPT4, education, Future, Future work, Jobs, teaching

Previous post

Unleashing AI Potential: OpenAI's Game-Changing Impact on Business Transformation

Next post

How Virtual Reality is Revolutionizing Business: Navigating the Technological Transformation

You may also like

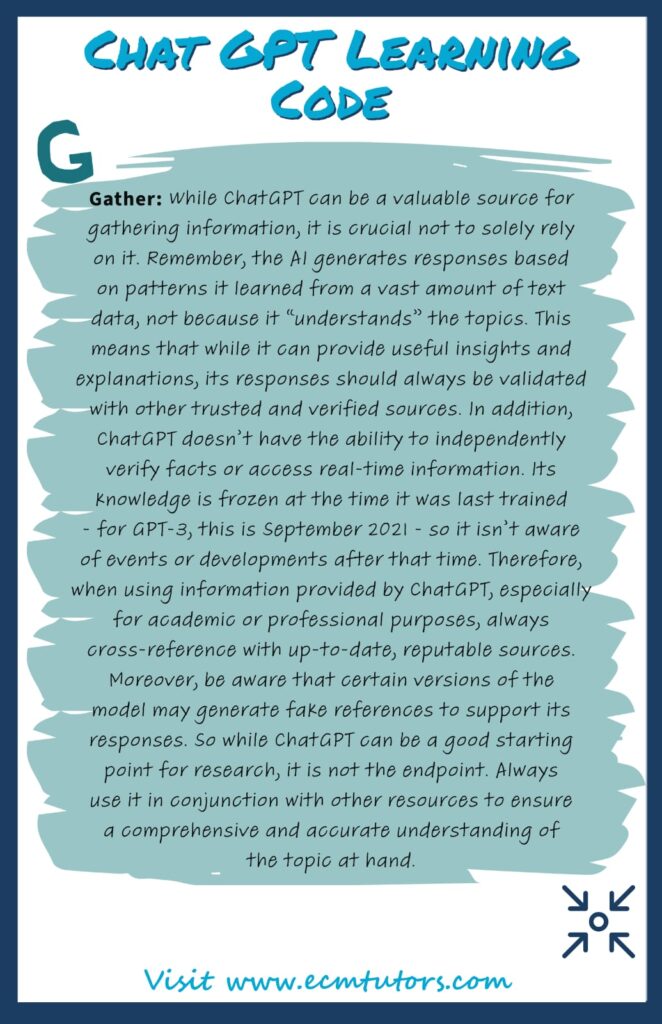

An Overly Simple, Non-techie Guide to Encourage AI Use for Learning.

Embracing AI in the classroom: ChatGPT, an Enriching Learning Tool

1 Comment